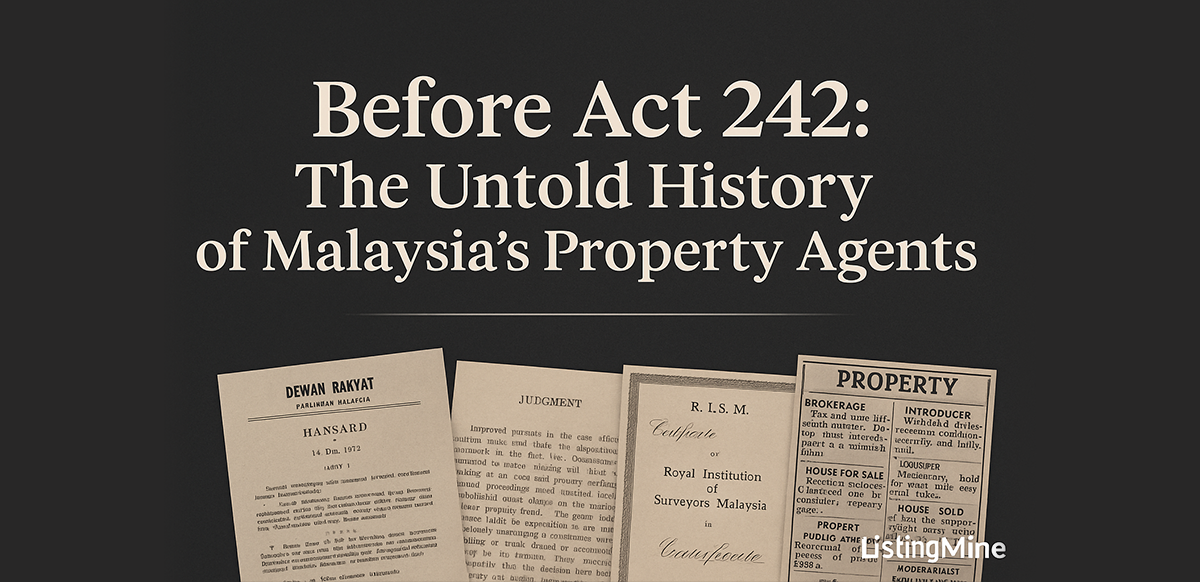

Before Act 242: The Untold History of Malaysia’s Property Agents

Malaysia's modern real estate industry, established by the Valuers, Appraisers and Estate Agents Act 1981 (Act 242), is officially less than 50 years old. Yet, property transactions have been happening here for more than a century.

So what exactly were the "property agents" doing before the 1981 Act created today's regulated licensing system?

Most people assume estate agency has always been a recognized profession.

It wasn't.

For most of Malaysia’s history, it was an informal trade—a shadow market with no structure, no standards, no licensing, and almost no institutional memory. This article reconstructs that forgotten era using parliamentary debates, legal cases, RISM archives, and dusty newspaper ads—the closest thing we have to a pre-1981 "record."

What emerges is a picture of an industry that existed long before regulation, but never as a profession.

1. The Reality Before 1981: An Industry Without a Legal Name

Before Act 242, "property agent" was not a legal category.

There was no license to apply for. No professional title to earn. No central board maintaining standards. Anyone could act as an intermediary in a property transaction.

Some called themselves "brokers."

Some were "house introducers."

Many were part-timers: clerks, taxi drivers, contractors, or retirees who simply knew someone selling a house.

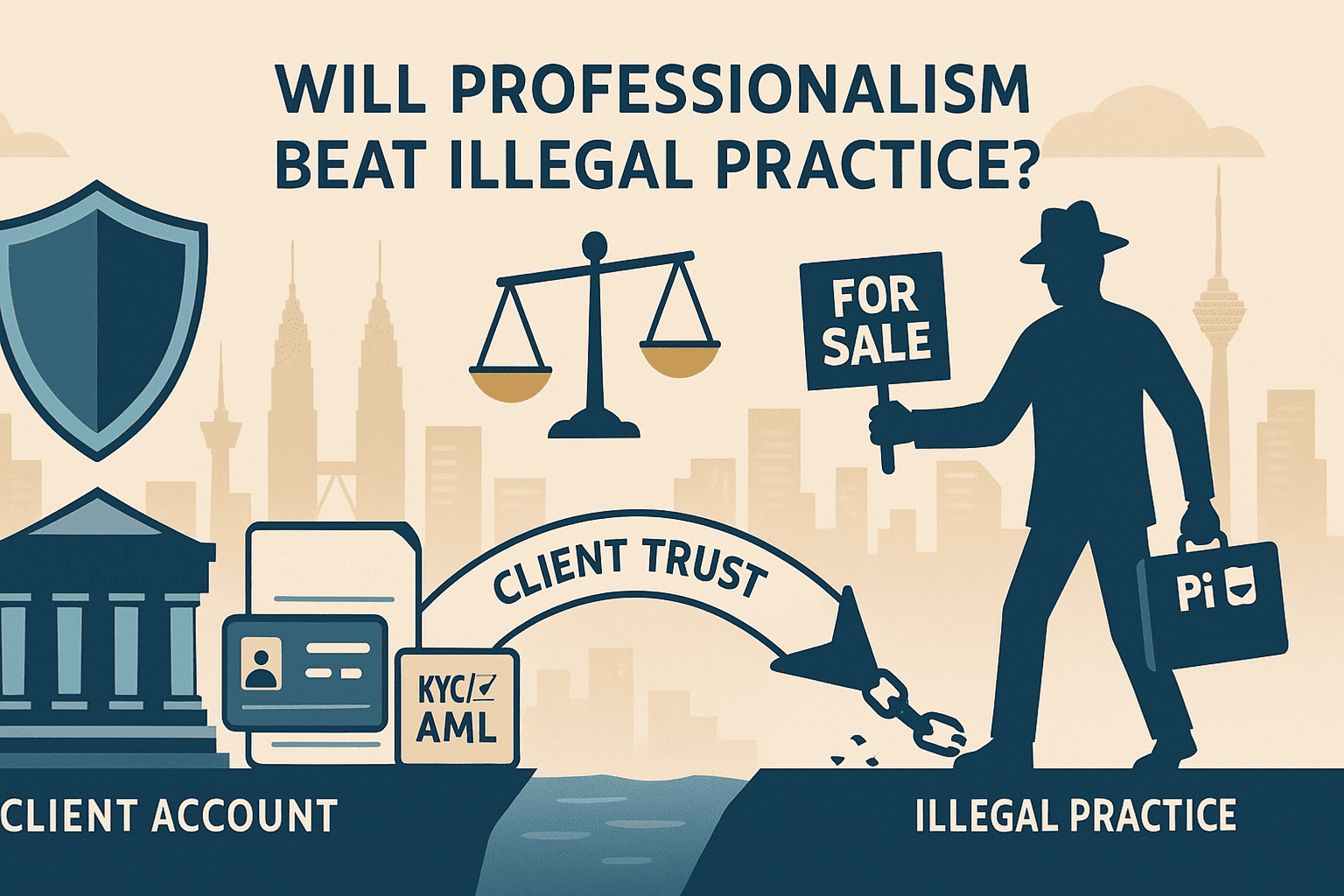

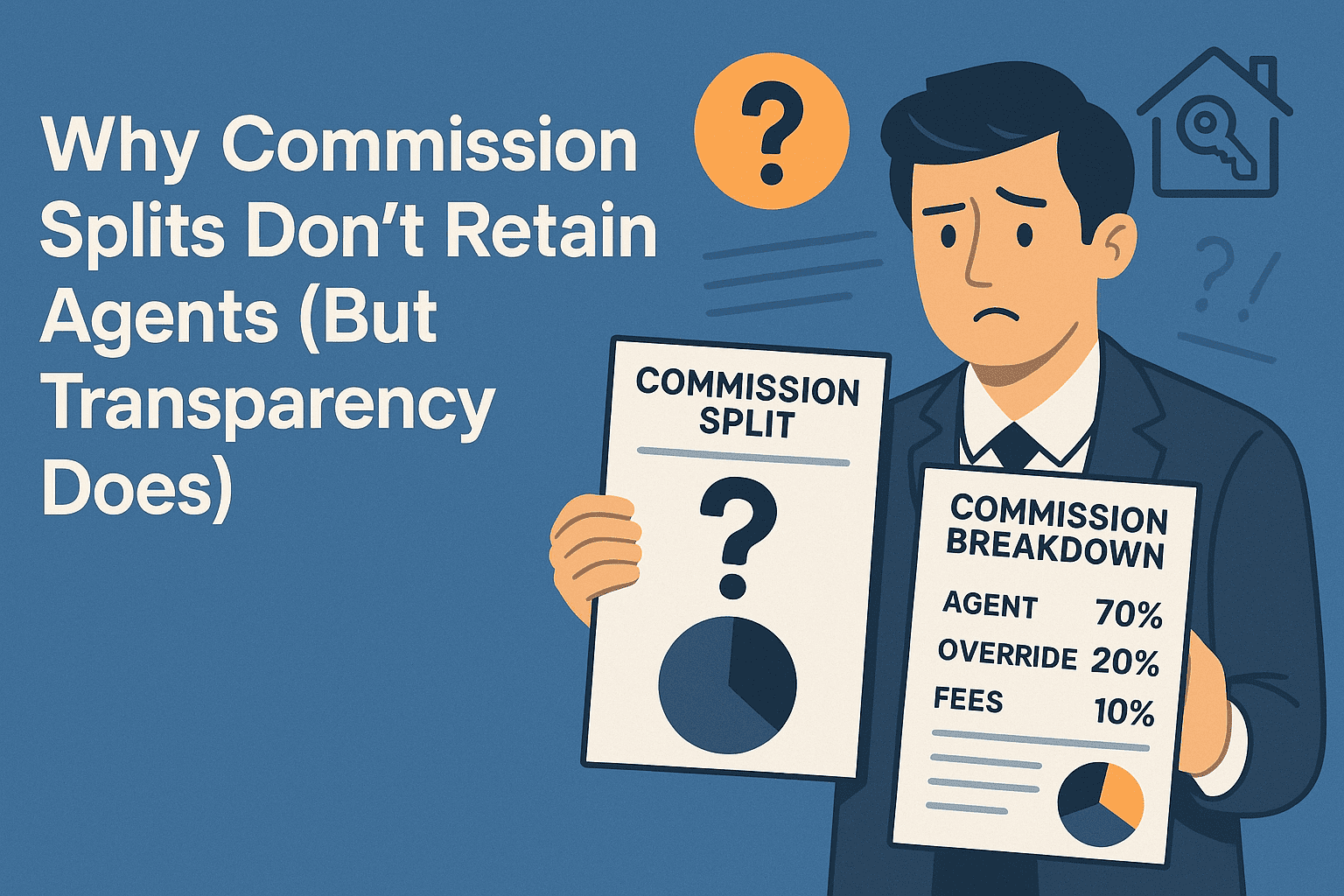

They operated in a completely open, unregulated market. There were no rules governing commission, client representation, fiduciary duties, deposit handling, conflict of interest, or exclusive listings.

This absence of law was not an oversight; it was normal. The law simply did not regulate the role, leaving the consumer completely exposed.

2. The Great Imbalance: Professionals vs. Middlemen

While brokers operated informally, the valuation profession was already structured and respected. Government valuers, chartered surveyors, and the Royal Institution of Surveyors, Malaysia (RISM, founded 1961) created a recognized professional track for valuation and appraisal.

Estate agency was deliberately excluded from that system.

This fundamental imbalance—professionals in valuation, unregulated middlemen in agency—shaped the next four decades of the Malaysian property landscape.

3. How Property Was Actually Transacted (1950s–1970s)

In the absence of a professional real estate body, three groups handled the bulk of transactions:

3.1. Lawyers: The Primary Facilitators

Since conveyancing is inherently a legal process, lawyers were often the main facilitators. Many also actively introduced buyers and sellers, effectively performing the agent's role today, but with legal oversight.

3.2. Brokers and Middlemen: The Unofficial Market

This group was the true predecessor to today’s agents. Their methods were basic and informal:

- Handwritten notices and classified ads in newspapers.

- Word-of-mouth and neighbour-to-neighbour networking.

- Manual collection of deposits and informal, often verbal, negotiation.

There were no formal, standardized contracts. Most deals relied solely on personal trust and oral agreements, making fraud easy and resolution nearly impossible.

3.3. Developers: Direct Sales and Informal Networks

As urban housing expanded in the 1960s and 1970s, developers sold directly to buyers and leaned heavily on these informal brokers to bring traffic. Nothing was standardized; everything depended on personal relationships.

4. Evidence from the Chaos: What the Hansard Reveals

Between 1970 and 1980, Malaysia’s Parliament repeatedly debated the crisis. The Hansard (official parliamentary record) documents a litany of complaints:

- Fraud by unqualified brokers. Buyers losing deposits. Sellers misled by middlemen. Unauthorized people posing as agents. Brokers disappearing after collecting money.

MPs described the situation as harmful to consumers and devastating to public confidence. These debates—arguments for why regulation was necessary—are the earliest formal documentation that the brokerage industry even existed. The chaos itself became the proof.

5. Evidence from the Bench: Agency as a Common-Law Contract

Legal cases from the 1960s–1970s show how the courts viewed these informal transactions:

- Commission disputes were rife, often based on oral agreements.

- Courts treated brokers like any other informal commercial agent.

- Misrepresentation was rampant. Anyone could claim commission if they merely "introduced" a buyer.

The critical difference: There was no discipline mechanism. The courts could punish fraud, but they had no license to revoke and no standards of conduct to enforce.

6. The Market’s Silence: Why No Records Exist

The absence of professional literature before 1981 is not an accident—it is the direct symptom of the industry’s structure:

- No profession: Nothing to document.

- No licensing: No central records existed.

- No training path: No academic discipline formed.

- No governing body: No institutional memory developed.

Estate agency, as we know it today, simply did not exist. The lack of documentation is the documentation. The silence is the evidence.

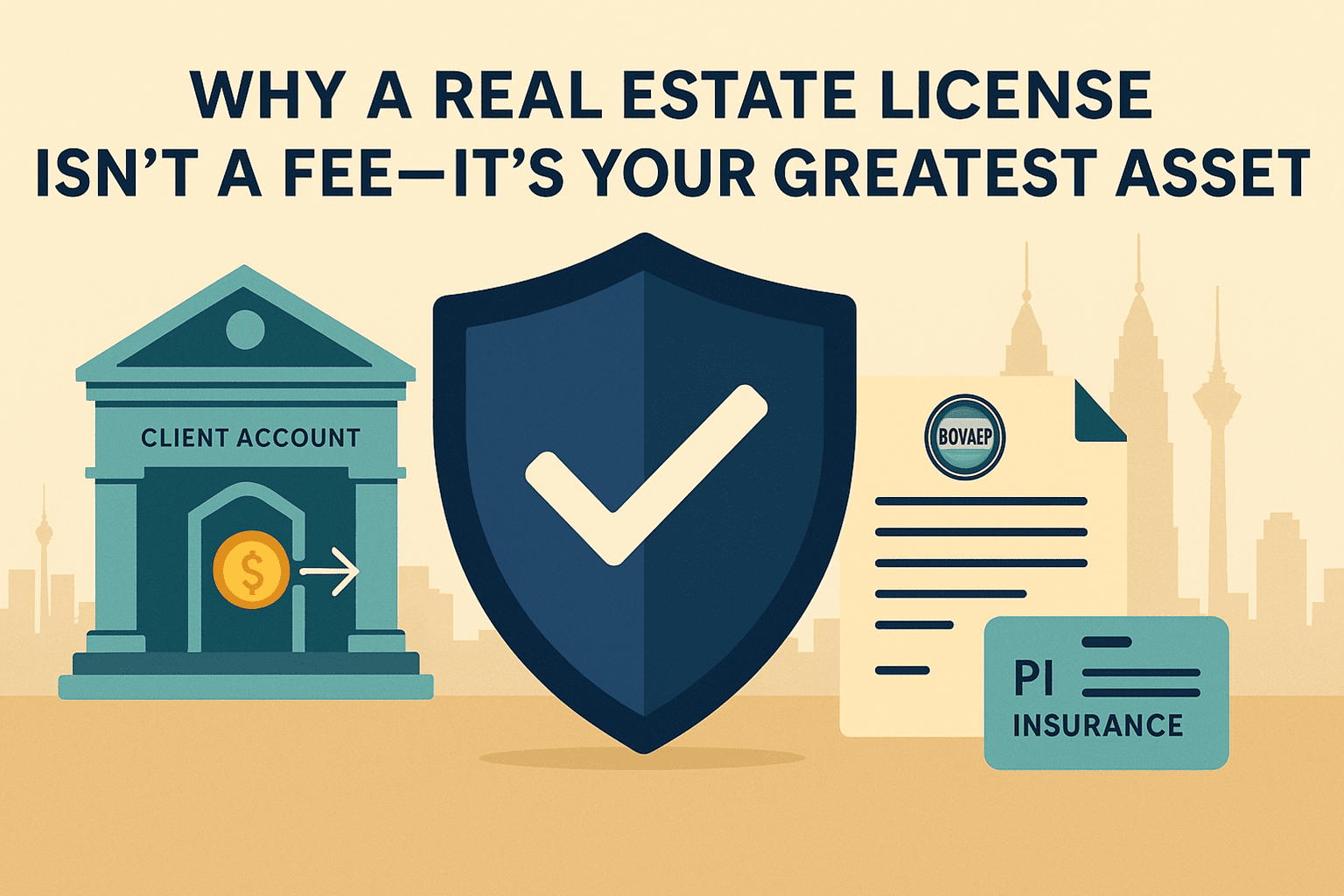

7. 1981: The Birth of a Profession

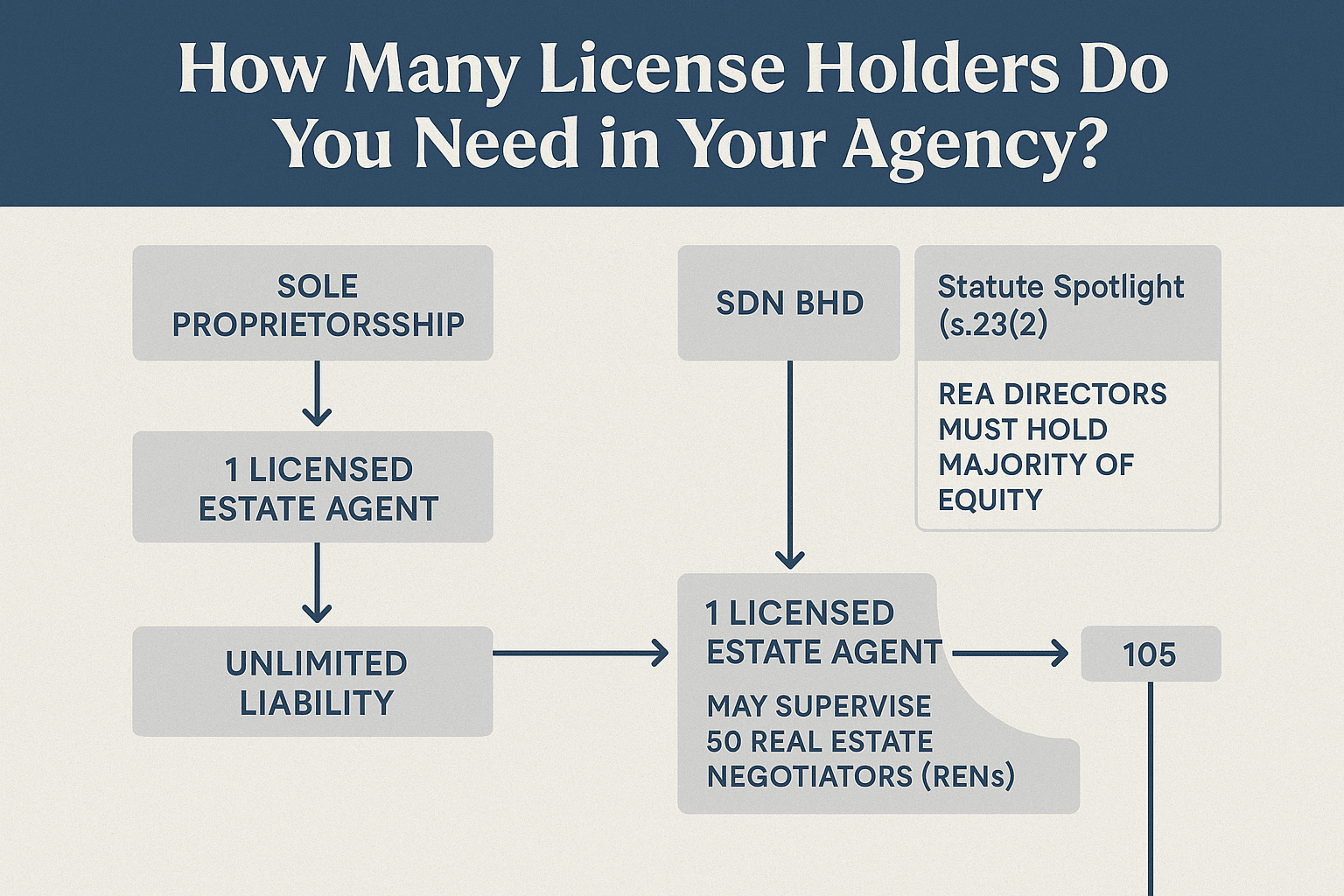

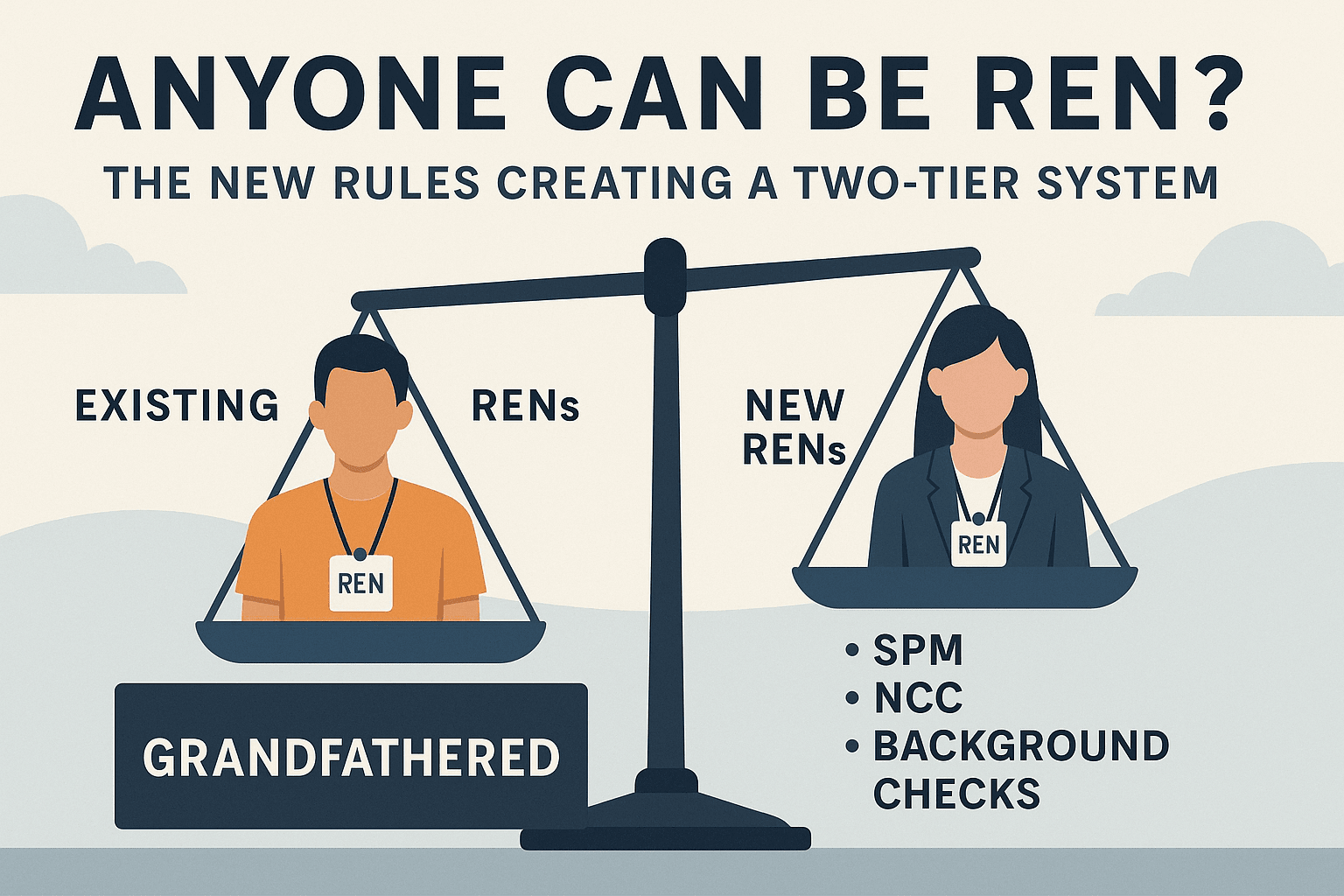

Act 242 changed everything. For the first time, Malaysia legally defined: what an estate agent is, who can practise, how to become licensed, and what standards they must follow.

It created BOVAEP, introduced rigorous examinations, issued licenses, and established disciplinary powers. This was the moment estate agency became a true profession, evolving from a market behaviour into a formalized industry.

Everything before Act 242 was pre-history. Everything after it was nation-building.

8. Why This Pre-History Matters to Malaysia Today

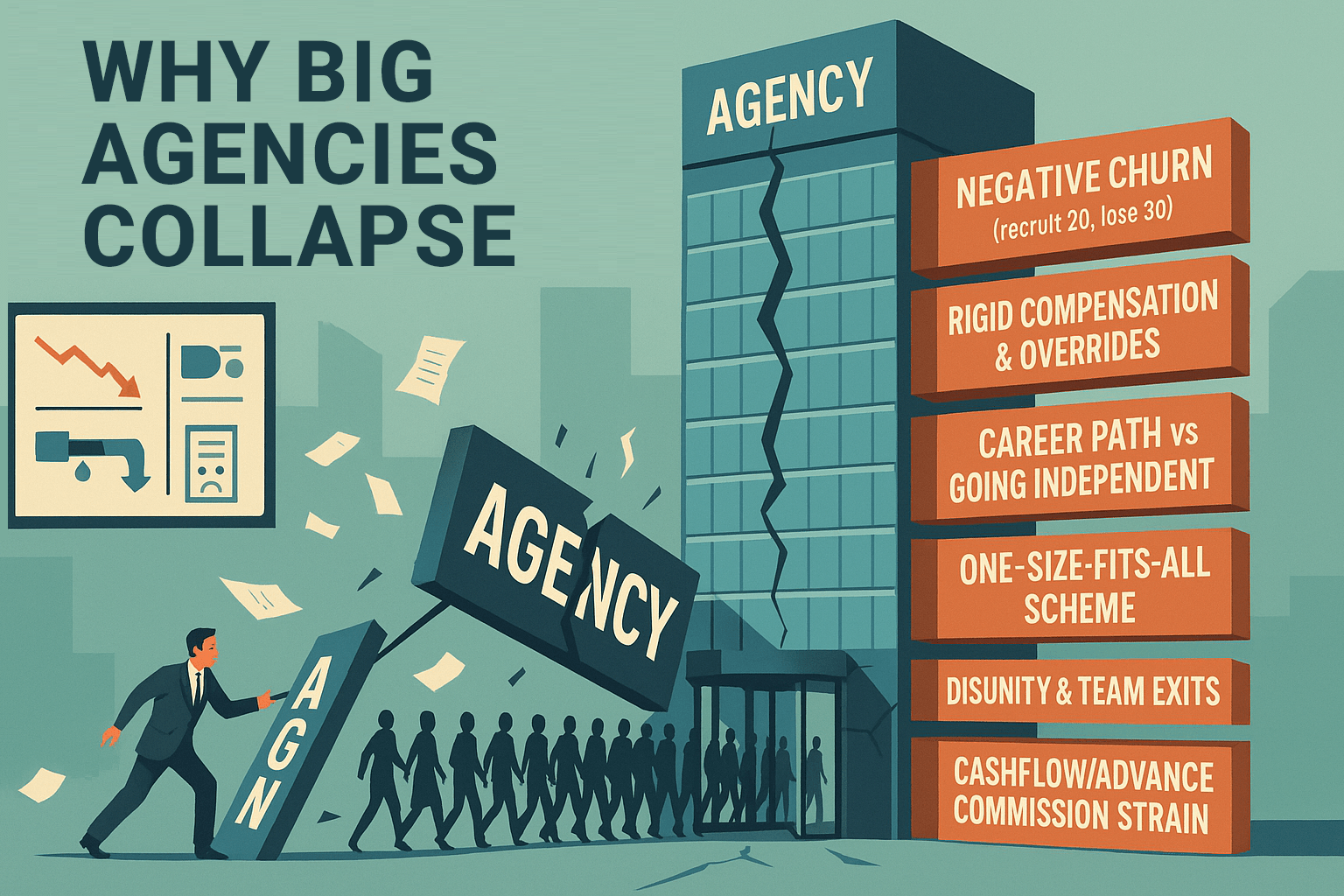

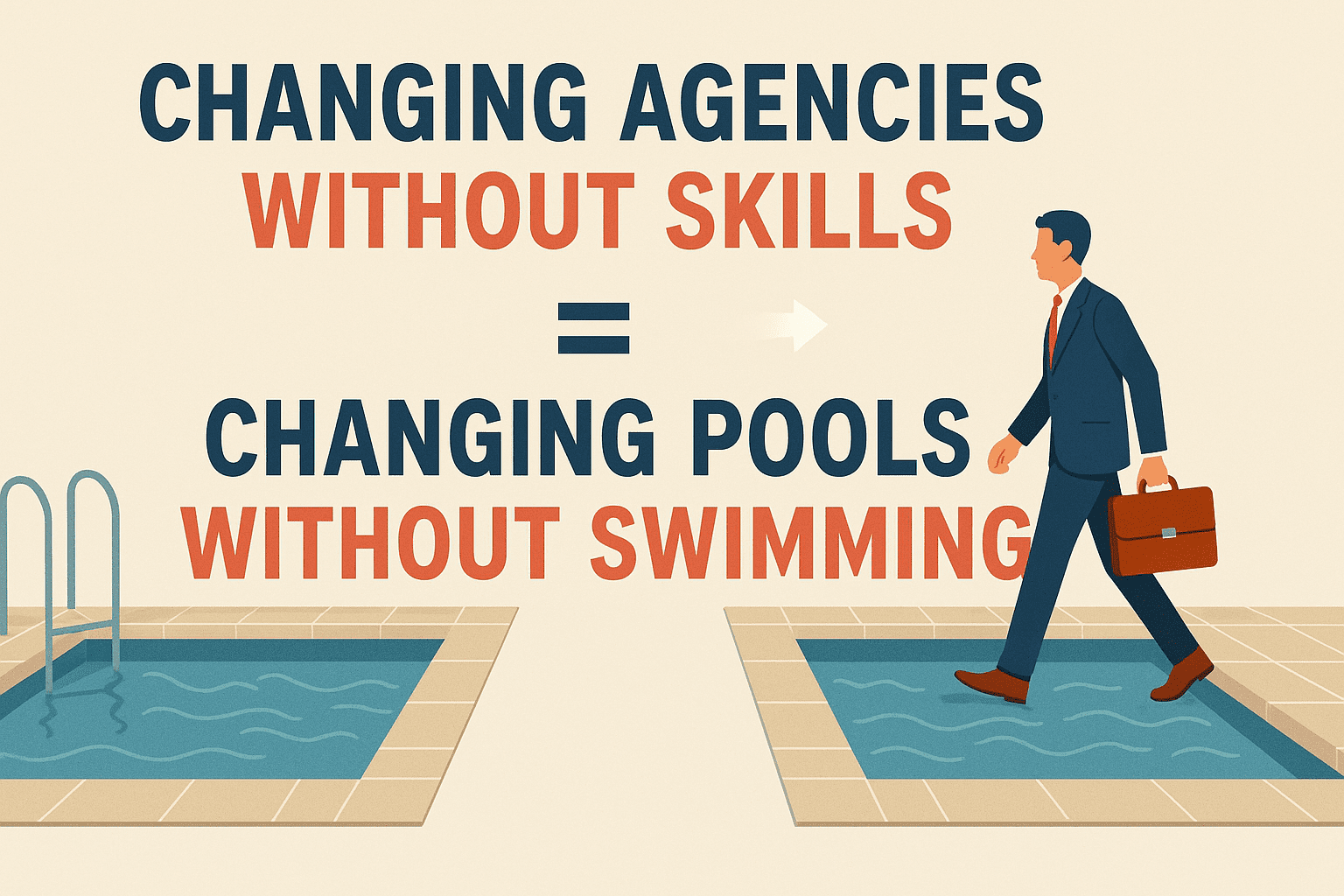

Understanding this forgotten era explains the deep-seated structural issues that plague the industry now:

| Modern Challenge | Inherited Legacy |

|---|---|

| Mistrust & Low Cooperation | Decades of informal, unregulated, zero-sum competition. |

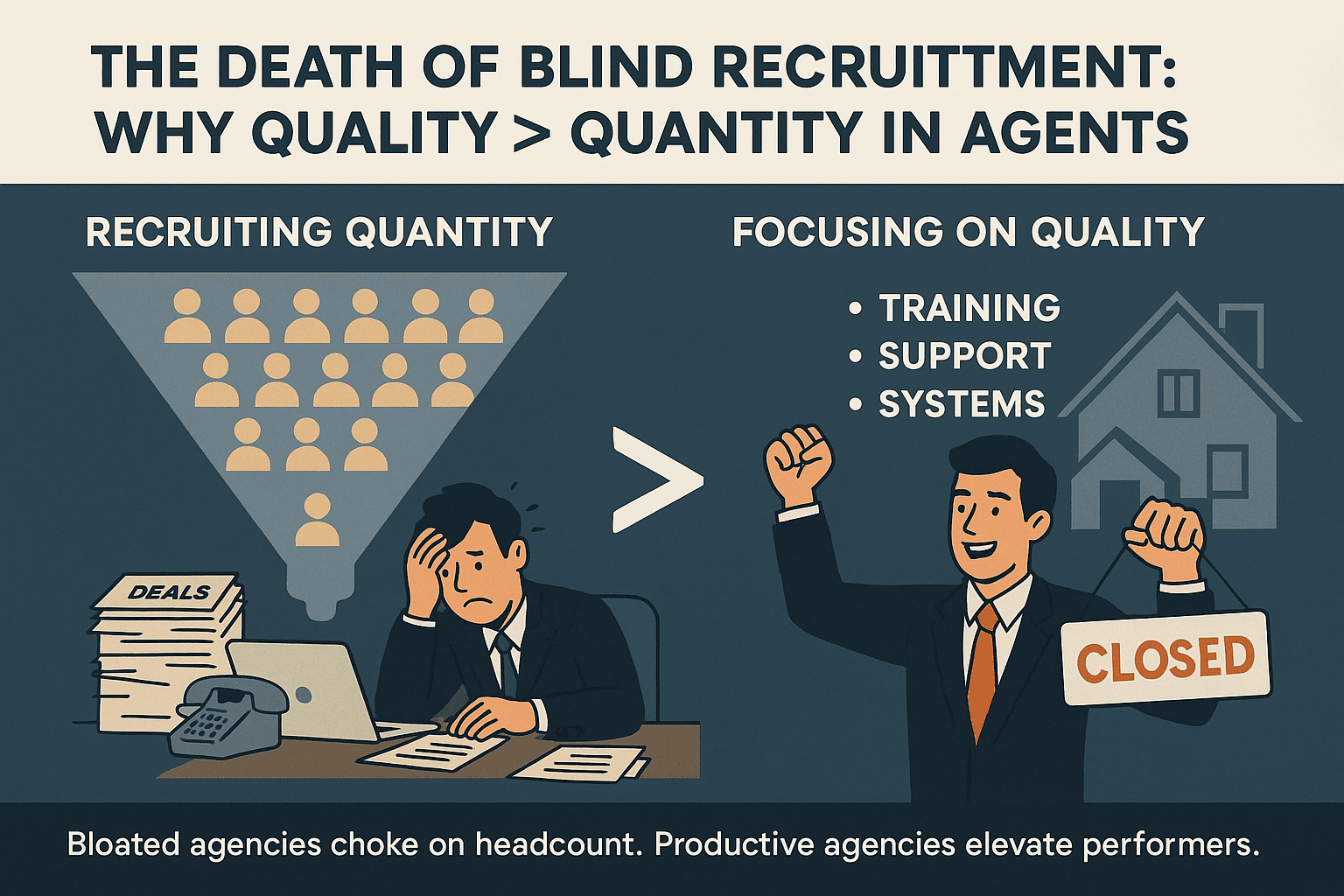

| Fragmented Agency Structures | The old system depended on individual, not cooperative, networks. |

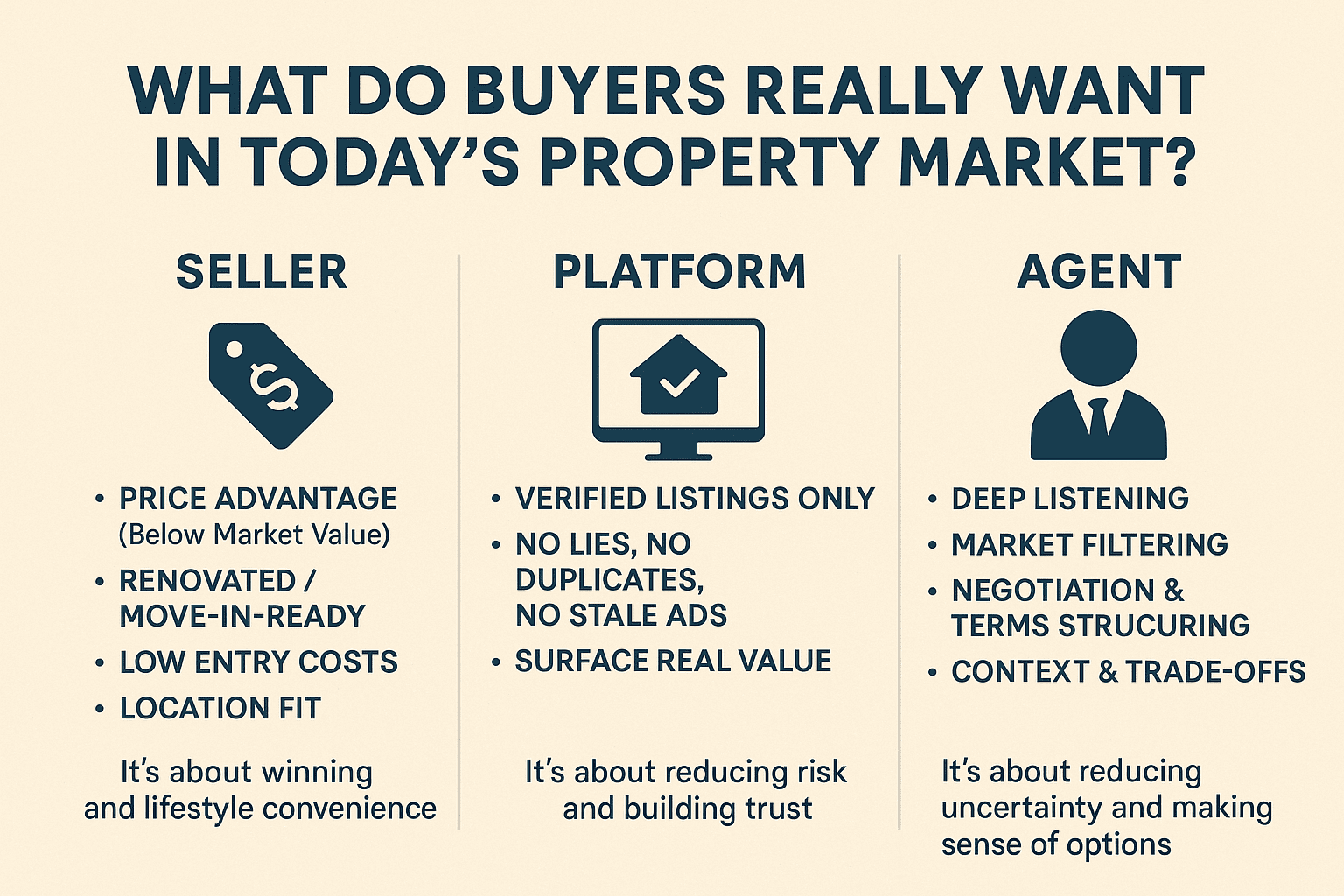

| Fake Listings & Data Issues | No tradition of verified, standardised data or fiduciary duty. |

| Lack of Professional Identity | An inherited DNA of being an informal "middleman," not a licensed professional. |

Malaysia’s modern industry did not start with a strong foundation; it started incorrectly, rooted in informal brokerage rather than professional intermediary work. That DNA is still visibly impacting efficiency and consumer confidence today.

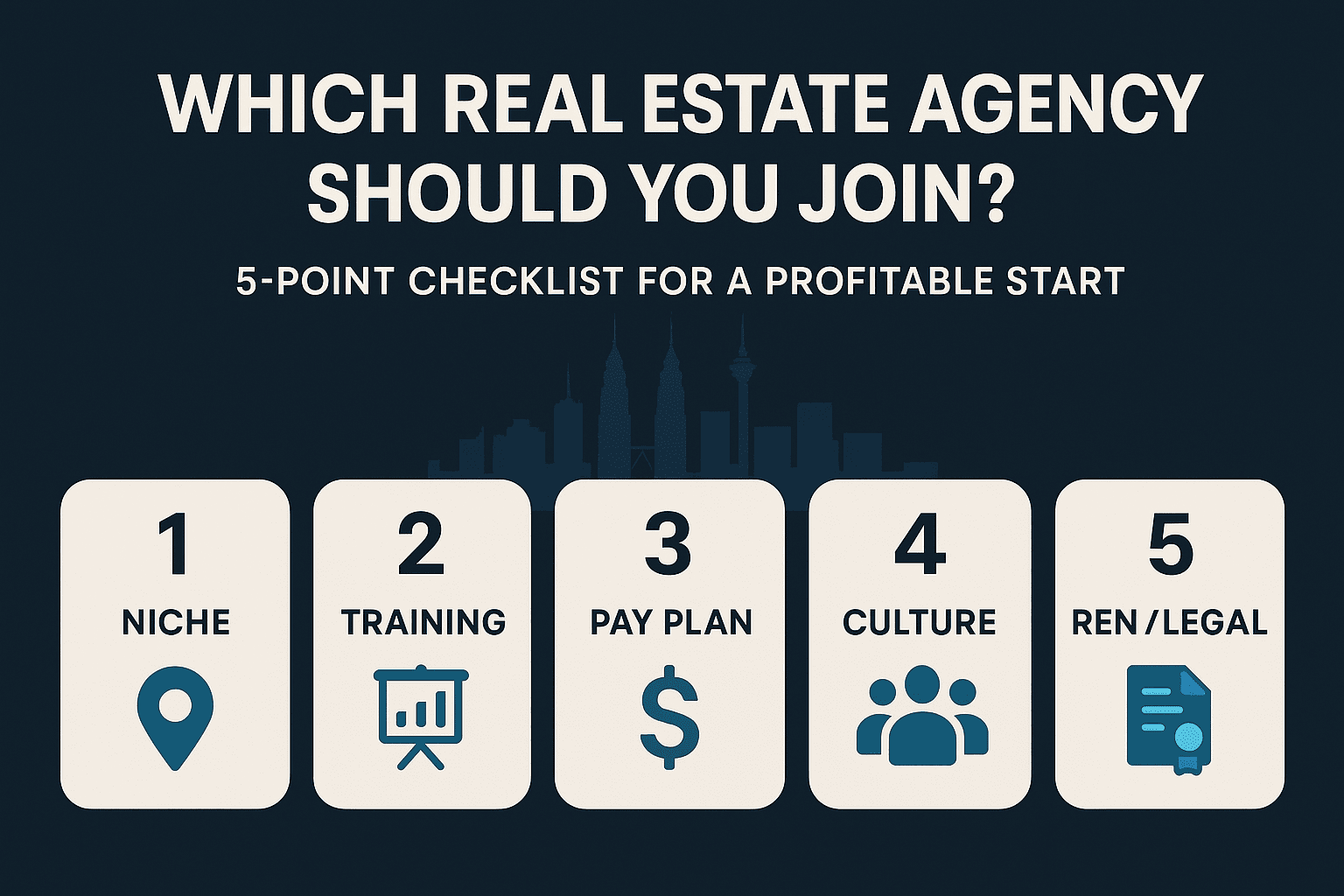

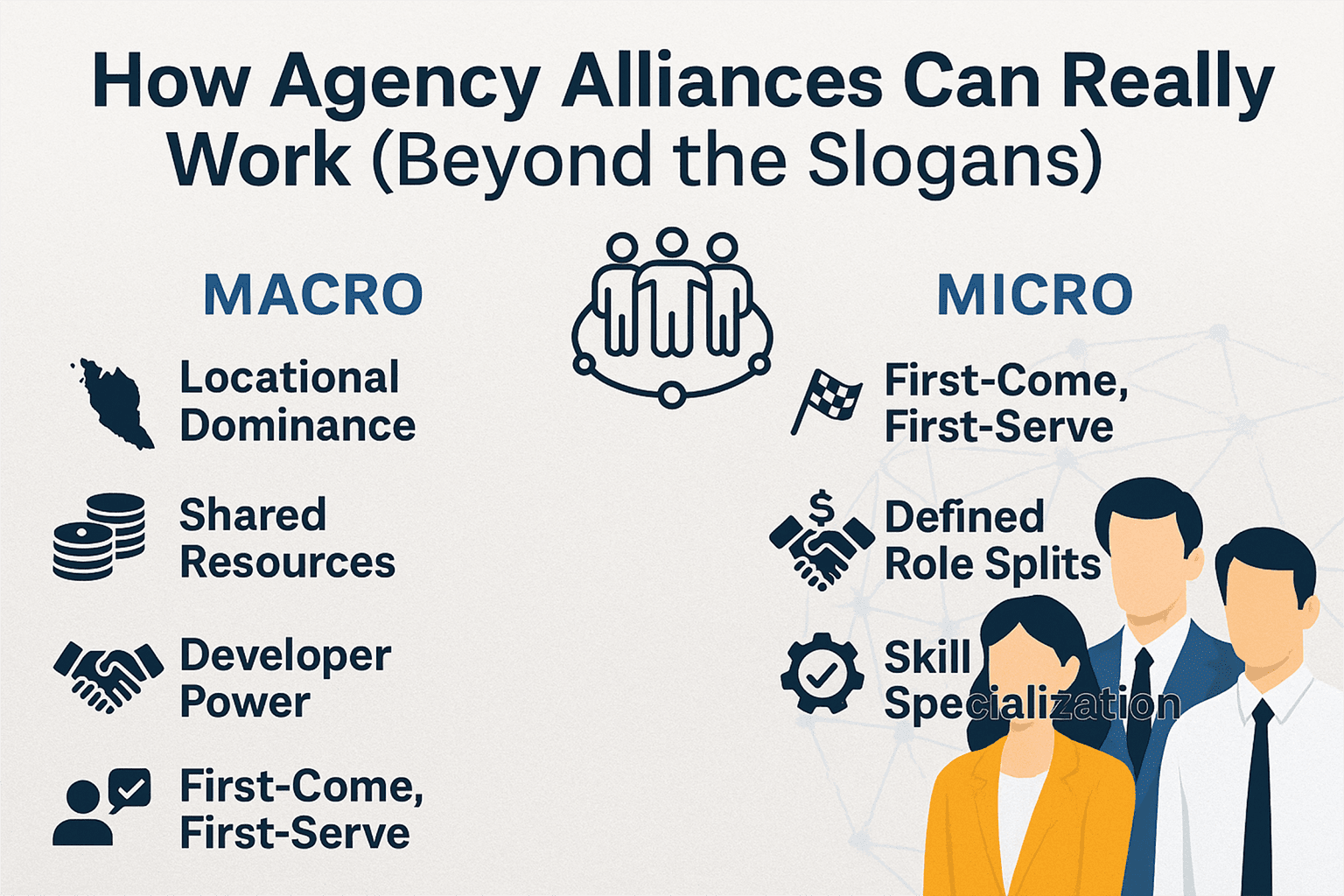

To truly evolve beyond this pre-1981 legacy, the industry must transition from being merely regulated to being institutionally modernized. This requires:

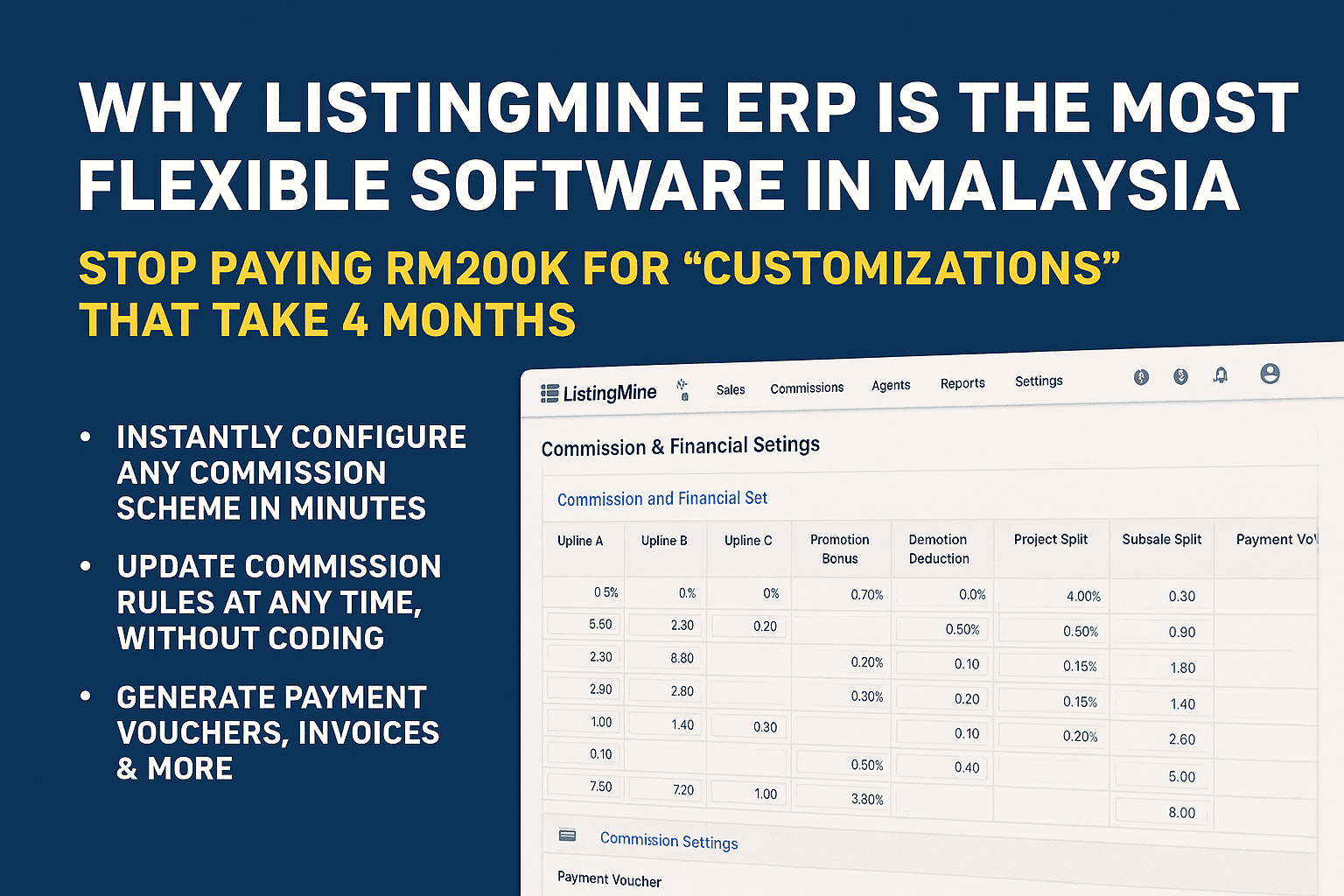

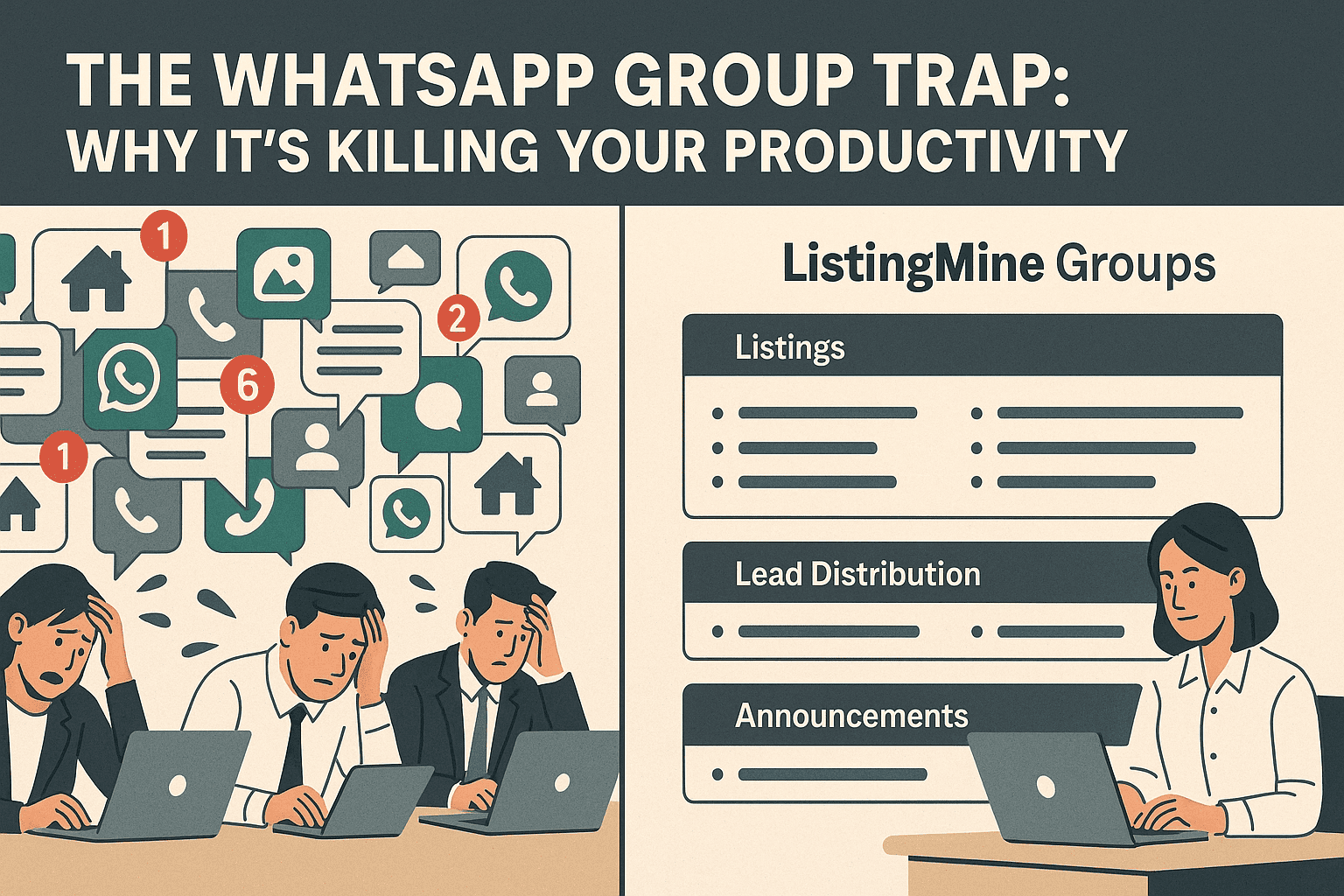

- Verified Inventory and Data Integrity: Ending the chaos of unverified listings.

- Professional Systems: Implementing standardized workflows and modern governance.

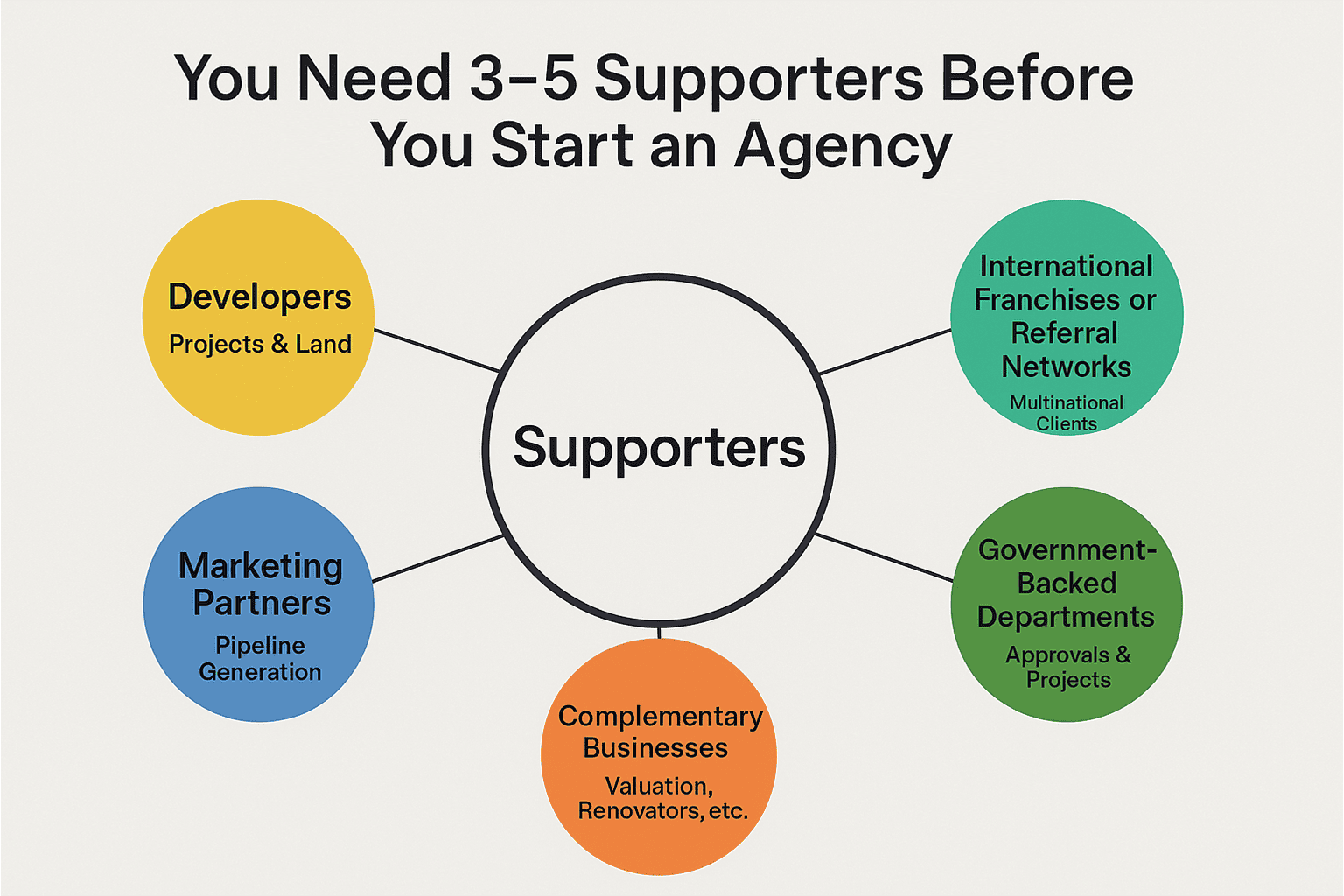

- Cooperation Infrastructure: Moving away from a competitive-only model toward shared, structured networks, which is fundamental to re-architecting the entire market.

Act 242 marked the beginning of professionalism. The next evolution, driven by data, technology, and governance, will mark the beginning of true modernization.