The GRR Dilemma: The Missing Law — To Sell or Not to Sell?

Why Guaranteed Rental Return projects expose Malaysian agents to moral, financial, and regulatory risks.

1. The Seduction of a “Guarantee”

Guaranteed Rental Return (GRR) projects are built to sound irresistible:

“Buy this property and enjoy 7% rental returns guaranteed for five years.”

For many first-time investors, that sounds like financial security — predictable income in an uncertain market. But behind that polished promise lies a hidden truth: the “return” isn’t genuine yield. It’s a rebate of the buyer’s own money, hidden inside an inflated selling price.

In other words, the developer quietly marks up the price so they can later pay the buyer back — with the buyer’s own capital.

It looks like income.

It behaves like rent.

But economically, it’s just a refund dressed as profit.

2. The Legal Vacuum: Malaysia’s Blind Spot

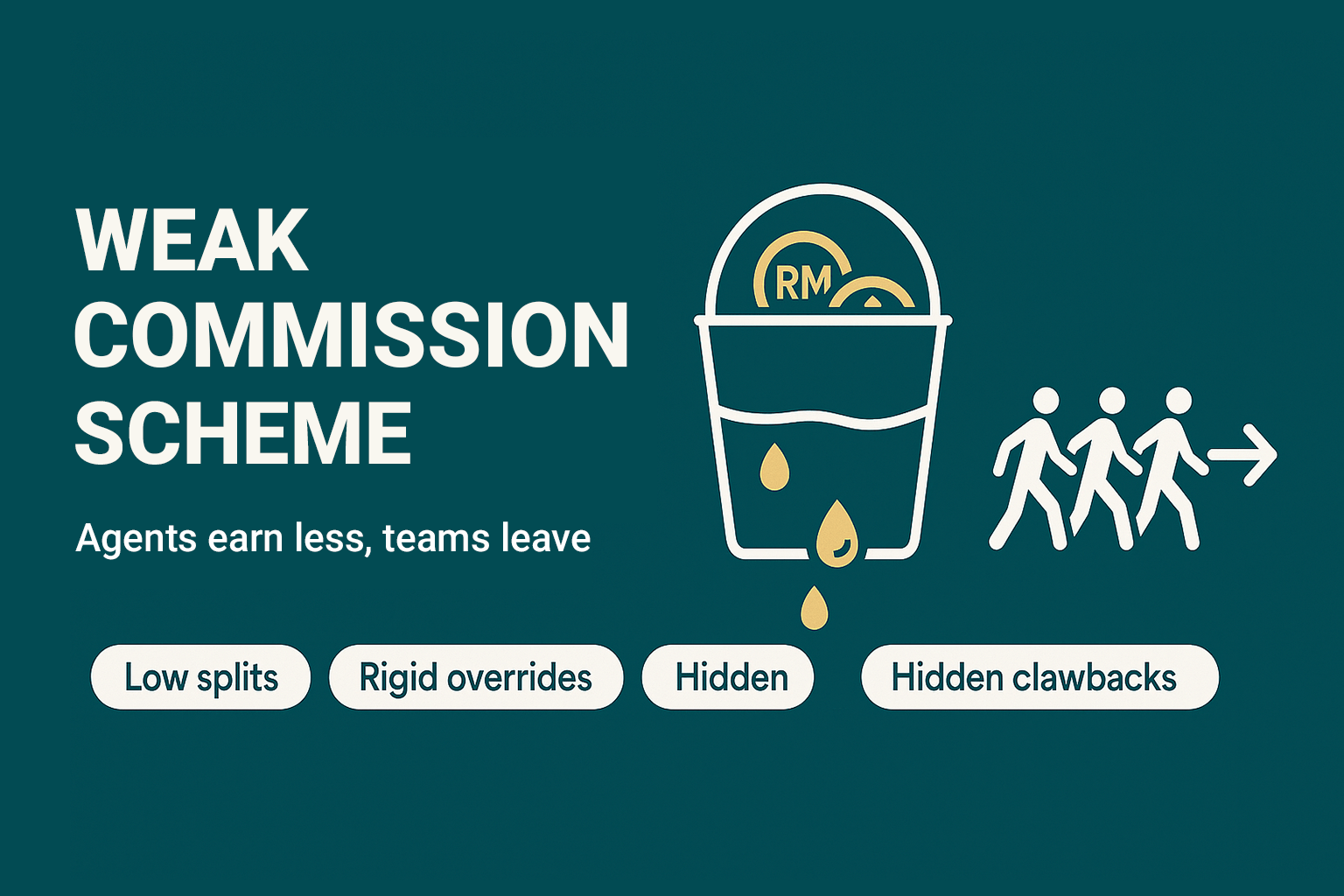

Malaysia has no dedicated law to regulate Guaranteed Rental Return (GRR) schemes. Developers are therefore free to:

- Inflate selling prices to fund the so-called “guarantee.”

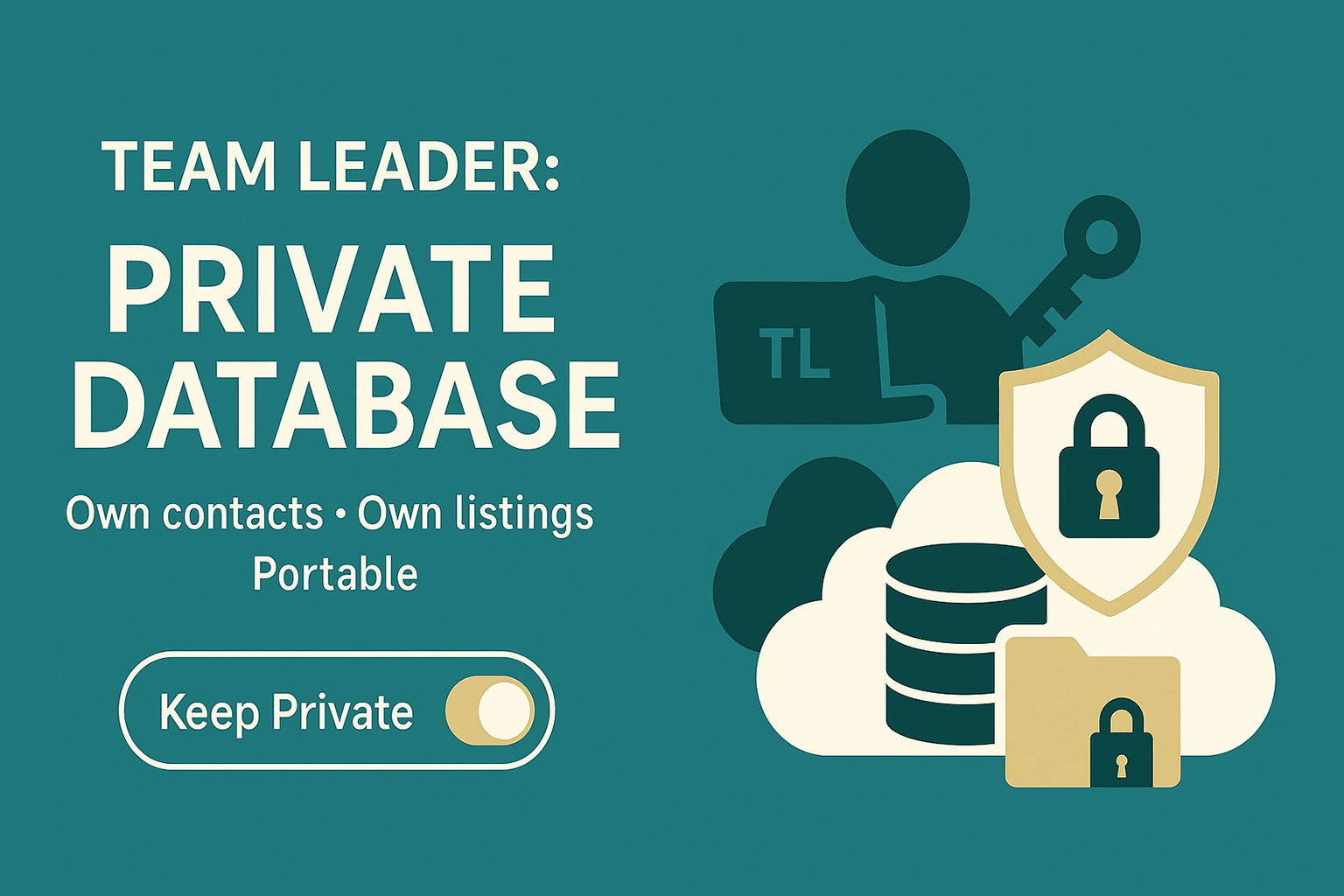

- Channel rental obligations through subsidiaries created solely for that project.

- Prematurely wind up those subsidiaries once the GRR funds run dry — often before the promised payout period ends — leaving investors with no recourse when payments stop.

The winding-up itself isn’t illegal. What makes it dangerous is the absence of legal safeguards preventing developers from diverting GRR funds to other uses, or from dissolving the paying entity mid-promise. Buyers simply have no statutory protection once that happens.

To make matters worse, many developers add a secondary charge at completion — commonly called a “renovation fee” or “furnishing package.” On paper, it appears optional, but in practice, it’s positioned as a mandatory condition to “activate” the GRR. Buyers are told that this fee allows the developer to “prepare” the unit for tenants, but in reality, it simply recycles more buyer capital to fund the rental payouts.

This means the buyer is not only overpaying upfront through an inflated purchase price but also topping up again upon completion to sustain the illusion of a guaranteed yield. It’s a loop of self-financing disguised as passive income — and every ringgit of it sits outside any statutory trust or escrow protection.

To make matters even worse, many investors perceive GRR income as “cash flow,” without realising that the price inflation and renovation fee together increase their loan amount, upfront cost, and interest exposure. Over a 30-year mortgage, the compounded interest on these inflated amounts can quietly exceed the total “guarantee” received.

If the market remains stagnant — as it often does once the marketing hype fades — the investor ends up paying higher instalments on an overvalued, over-leveraged property whose “guarantee” can vanish the moment the GRR subsidiary is wound up.

By contrast, in the United Kingdom, similar schemes are treated as regulated financial products, not just property sales. The distinction matters: it subjects developers and marketers to strict financial-conduct standards, disclosure rules, and investor-protection requirements — all of which are missing in Malaysia.

3. How the UK Handles GRR-Type Schemes

a. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA)

In the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) governs all financial promotions and investment-related activities. Under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA), Section 21 states:

“Any invitation or inducement to engage in investment activity must be issued or approved by an FCA-authorised person.”

If a GRR project is marketed as a simple property sale, it may fall outside this rule. But if it’s structured as an investment package — pooling funds, offering a fixed return, or managed on behalf of investors — it becomes a Collective Investment Scheme (CIS) under Section 235 of FSMA.

At that point, the promotion becomes a regulated activity, meaning:

- The developer must be authorised by the FCA, or

- Its marketing materials must be pre-approved by an authorised firm.

This ensures the scheme is subjected to legal scrutiny, investor protection rules, and enforcement mechanisms.

b. The Conduct of Business Sourcebook (COBS)

The FCA’s Conduct of Business Sourcebook (COBS) — particularly Rule 4.2.1 — requires that all financial promotions be:

“Fair, clear and not misleading.”

That means you can’t advertise a “7% return” without explaining how that return is generated. If the return comes from an inflated price, not real rental income, that fact must be disclosed prominently. Failure to do so would constitute misrepresentation under FCA rules — a punishable offence in the UK.

c. The Client Assets Sourcebook (CASS)

The FCA’s Client Assets Sourcebook (CASS) sets rules on how authorised firms must handle client money.

- Segregated from company funds,

- Held in protected trust accounts, and

- Ring-fenced in case the firm becomes insolvent.

However, this protection only applies if the entity holding the money is FCA-regulated. Ordinary property developers — who are not authorised investment firms — are not automatically bound by CASS.

So while the UK framework protects investors when regulated firms are involved, unregulated property sales can still slip through. In short: ring-fencing is conditional, not universal.

d. The Estate Agent’s Legal Duties

Even if a GRR scheme sits outside financial regulation, UK estate agents are still bound by consumer law — specifically the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 (CPRs).

Under these rules (soon to be reinforced by the Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act 2024), it is a criminal offence to omit or hide material information that could influence a buyer’s decision. So if an agent fails to disclose that the “guarantee” is funded by an inflated price, they can be prosecuted for a misleading omission.

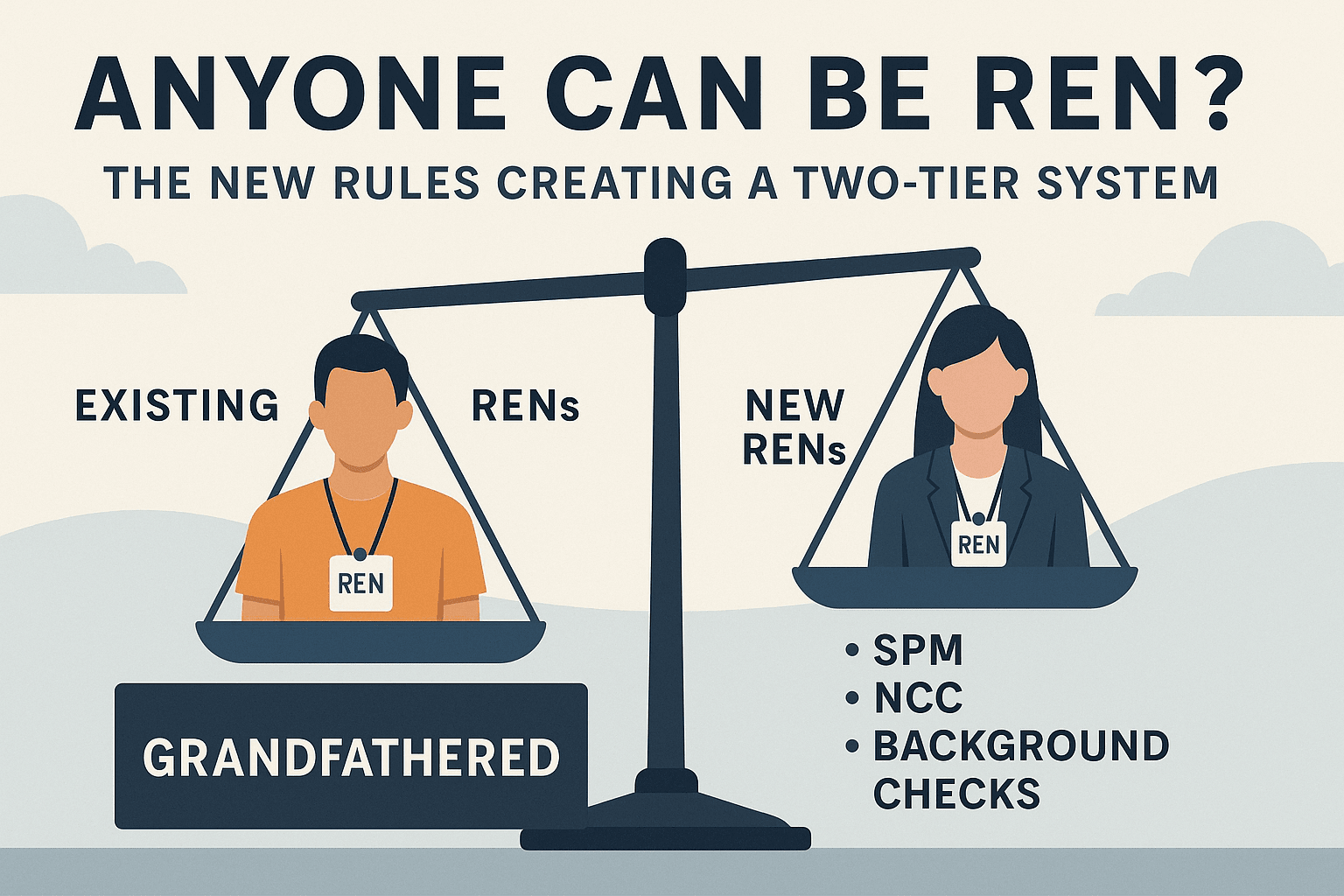

4. Malaysia: The Total Absence of Safeguards

In Malaysia, none of these guardrails exist. There’s no equivalent of the FCA, FSMA, COBS, or CASS. Developers can market “guarantees” without any requirement to prove how they’re funded or to segregate money in trust.

Once the special-purpose subsidiary is wound up, the buyer has no legal recourse. The “guaranteed rent” becomes a broken promise — perfectly legal, but practically worthless.

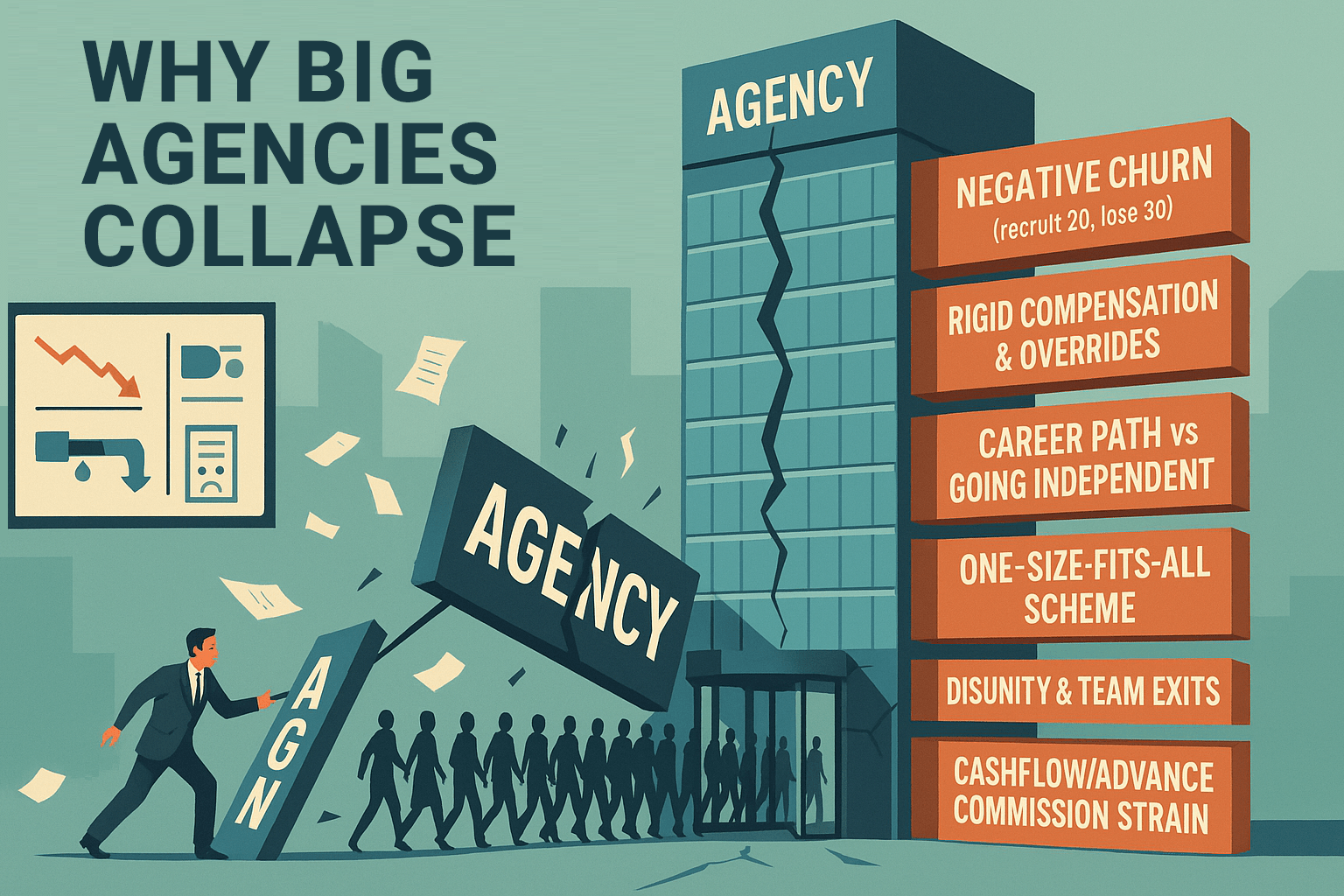

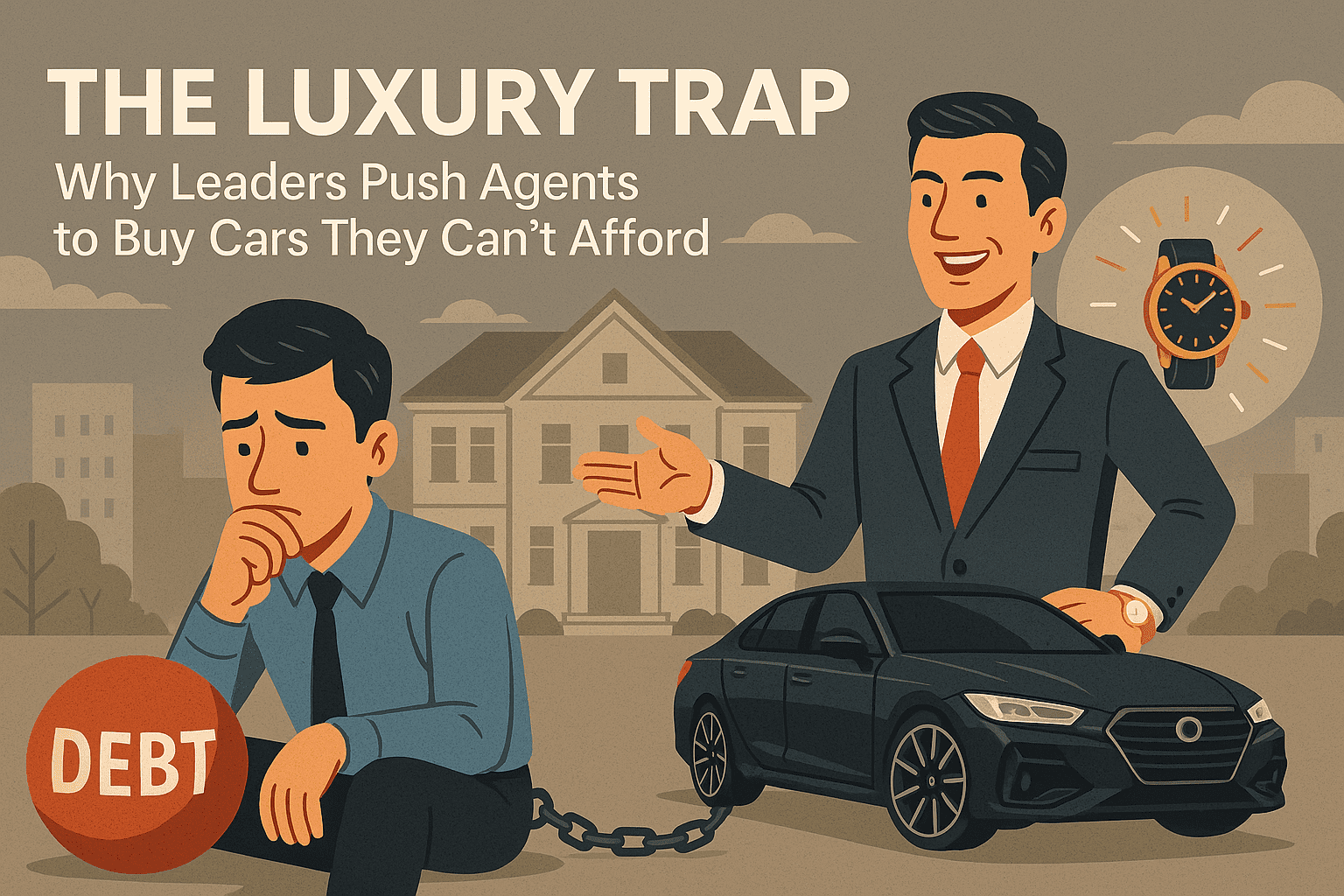

5. The Agent’s Dilemma: Sell or Walk Away?

This is where things get personal.

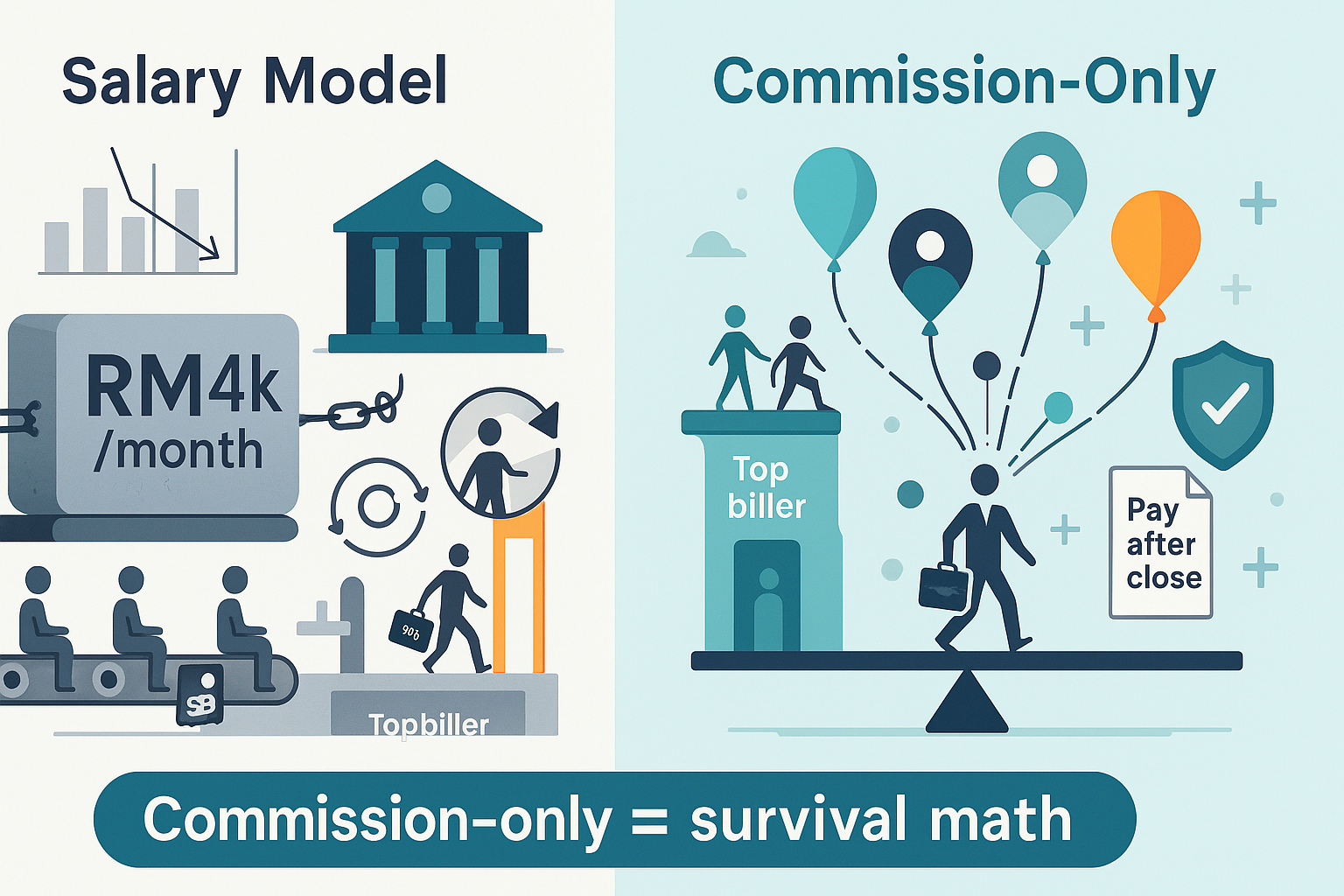

Agents are caught between commission and conscience.

- The developer is the paying client.

- The buyer is the trusting consumer.

- If you don’t sell, someone else will.

- If you do, you inherit the moral burden.

In the UK, the law acts as a referee.

In Malaysia, agents are left to referee themselves.

6. The Economic Reality Behind GRR

Let’s strip away the marketing and look at the mechanics using a simple example:

| Description | Amount (RM) |

|---|---|

| True market value (MV) | 500,000 |

| Selling price with “guarantee” (SP) | 600,000 |

| Built-in markup (reserve) | 100,000 |

| “Renovation / furnishing fee” (often compulsory) | 30,000–50,000 |

The RM100,000 markup and additional renovation fee are the fuel for the “guarantee.” In many cases, the first 1–3 years of the GRR are fully covered by these prepaid funds — not by genuine rental income.

What happens in practice:

- The developer collects the RM100k markup and a “renovation” fee at handover.

- That pool is used to pay the promised 7% return for the early years — often through a separate shell company or SPV.

- By Year 3 or 4, the reserve is depleted. Future payouts depend entirely on actual rental performance or partial top-ups combining rent plus what remains of the reserve.

- If real rental demand fails to meet the projected level, the GRR company defaults or winds up, ending the “guarantee” prematurely.

However, the payments often stop far sooner — sometimes within the first year. The company behind the guarantee is usually a separate legal entity with no capital, making any form of legal action pointless. Owners are suddenly stuck with mortgage repayments on empty units in an oversupplied market, causing rental rates and resale values to collapse. Entire projects have seen rapid price crashes and major financial losses for investors who believed the “guarantee” protected them.

Some developers attempt to sustain the illusion by offering units at below-market rents from Year 1, topping up with portions of the reserve to maintain the “7% yield” on paper. Eventually, the reserve thins out — and the final years’ payouts quietly disappear.

The hidden cost of borrowing your own money:

- That extra RM100k–150k (markup + renovation fee) is usually financed through the buyer’s mortgage. Over 30 years:

- At 4% interest, total extra interest ≈ RM70k–100k+.

- At 5% interest, ≈ RM90k–120k+.

So the buyer ends up paying interest on their own future “returns.” It’s financial recycling — not investment yield.

Resale impact:

If the market stays flat, resale gravitates toward true MV (~RM500k), leaving the buyer locked into a loss. They’ve financed the illusion of returns, only to discover that the guarantee was pre-spent before the first tenant even moved in.

Bottom line:

- Years 1–3 are funded by the buyer’s own markup and renovation fee.

- Years 4–5 depend on real rental and the developer’s survival.

- When the math breaks, the GRR company quietly disappears — and the investor is left with an overpriced property and a costly lesson.

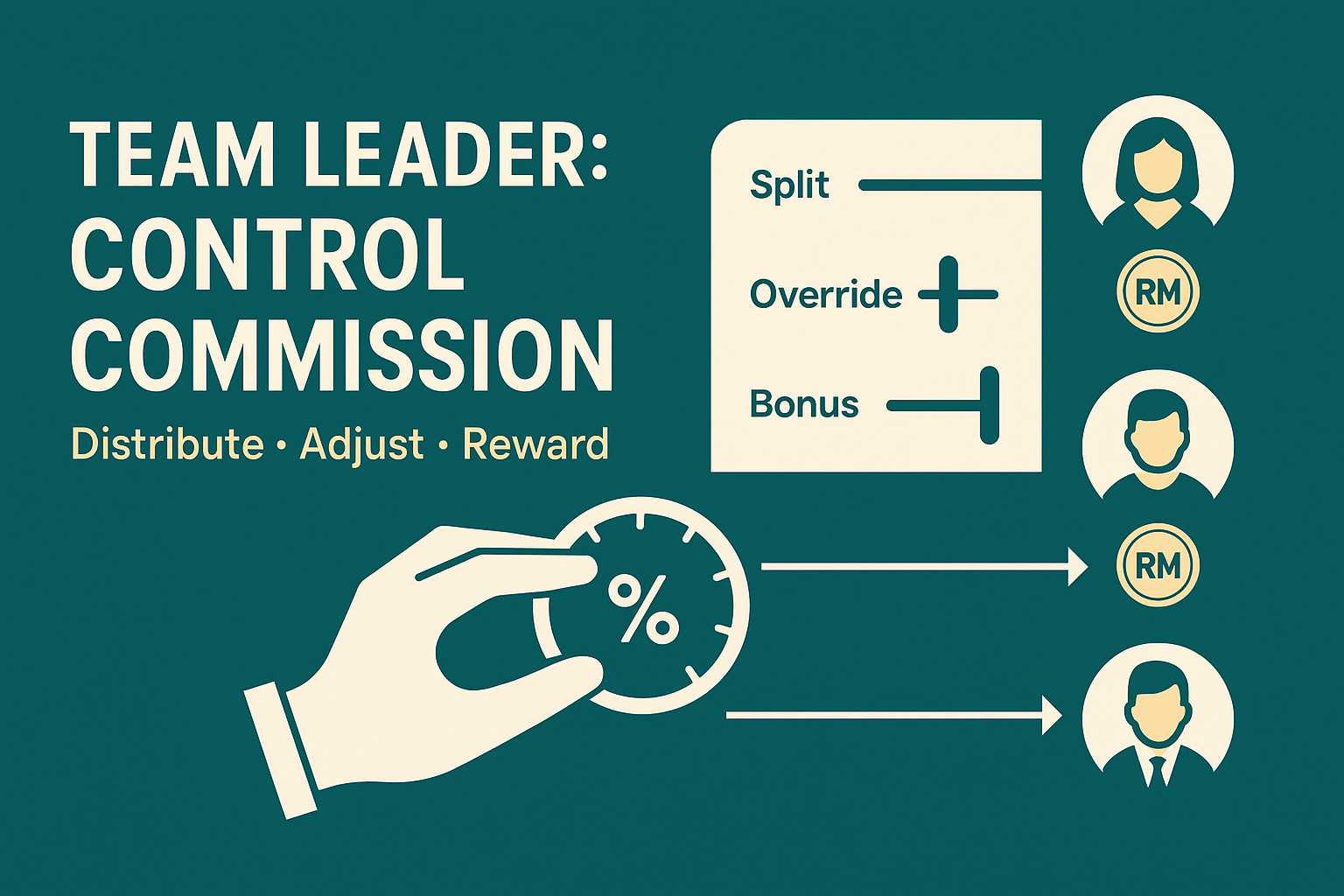

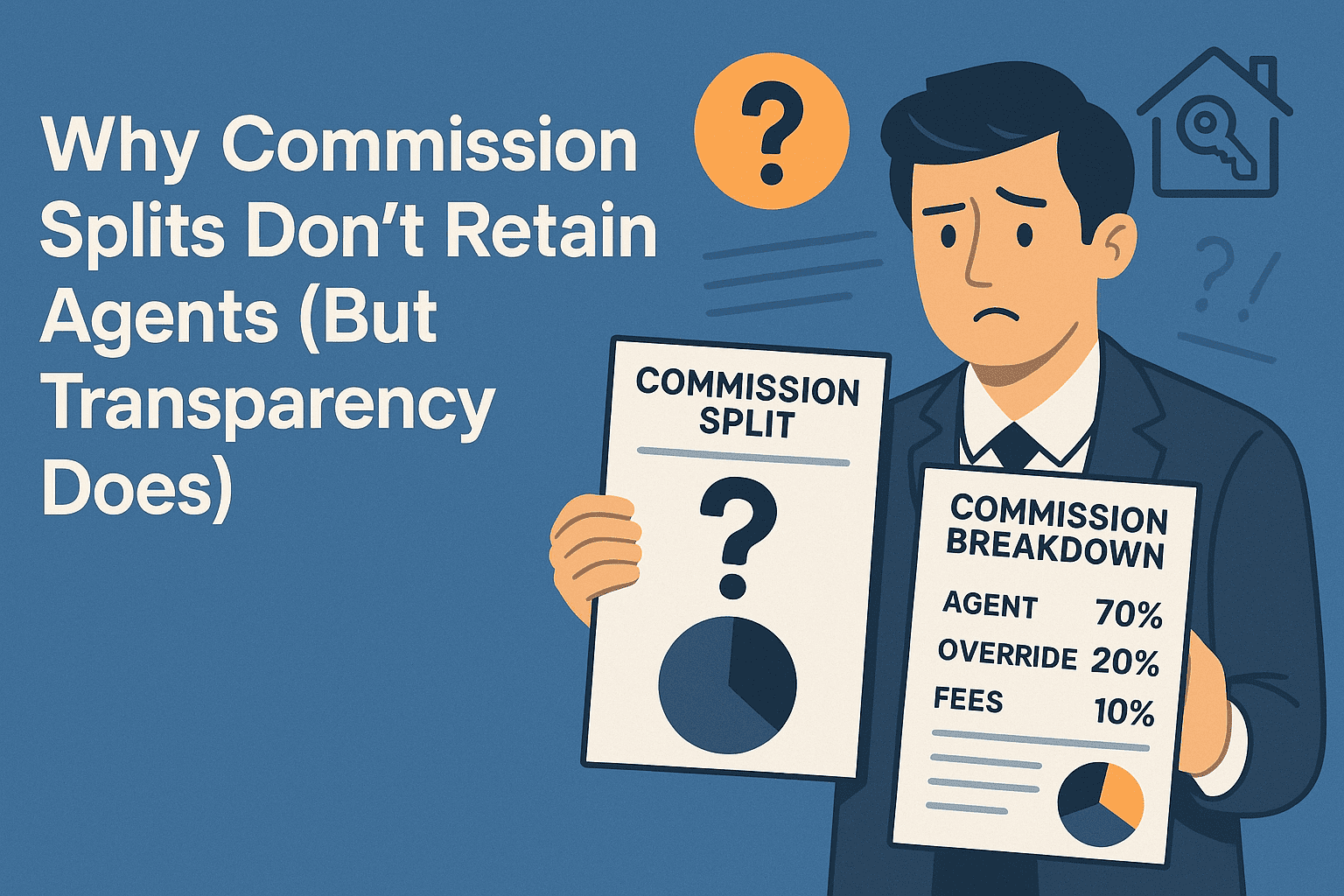

7. What Responsible Agents Should Do

Until Malaysia enacts proper GRR regulation, ethical agents must self-regulate.

- Disclose everything. Explain how the return is pre-funded from the selling price. Use plain words. Transparency is your best protection.

- Never claim legal safety. There is no statutory guarantee, no escrow, and no government-backed trust account in Malaysia.

- Protect your long-term brand. One bad sale can destroy years of credibility. Agents who outlast the market are those who refuse to endorse unstable products.

- Advocate reform. Malaysia needs its own version of the Financial Services and Markets Act (FSMA) and Client Assets protection rules (CASS) — to make sure investor money cannot be misused.

8. The Hard Truth: Lawless Doesn’t Mean Legal

GRR projects exist in Malaysia’s regulatory void — not illegal, but ungoverned.

That’s the danger: legality without accountability. Developers exploit this gap. Agents get blamed when it collapses.

Until Malaysia adopts similar investor-protection frameworks, the only real safeguard is ethical restraint.

9. Conclusion: The Real “Guarantee” Lies in Integrity

Guaranteed returns sound safe. But in Malaysia, they are certainty without security.

When the returns stop, the developer vanishes — and the buyer doesn’t call the government. They call you, the agent who made the sale.

That’s why the real question isn’t:

“Can I sell it?”

It’s:

“Should I?”

Because in an unregulated market, the only true guarantee is your own integrity.